Tax-loss harvesting (TLH) is a common practice we’ve discussed before, where an investor realizes losses to either offset capital gains or, preferably, to deduct investment losses against one’s current income.

Robo-advisors such as Betterment and Wealthfront trumpet their daily tax-loss harvesting strategies, handled by your future robot overlords. The robo-advisors tax-loss harvest by selling the primary ETF for each asset class and replacing it temporarily with an alternative ETF.

DIY investors can do the same easily, but in both cases, a key aspect to executing a successful tax-loss harvesting strategy is to swap your losers for a similar fund. For example, if you sell an index fund tracking the energy market for an index funding tracking the tech market, you’re not tax-loss harvesting. You’re simply changing allocations and likely making a mistake selling low and buying high. To successfully tax-loss harvest, you want to sell one fund and replace it with basically the same thing.

Unfortunately, the IRS wash sale rule won’t allow you to deduct a loss if you sell the security and immediately replace it with something that is “substantially identical”. The IRS hasn’t provided guidance as to what is “substantially identical”. Not surprisingly, the question comes up a lot when looking for suitable tax-loss harvesting partners. Tax advisors have different opinions.

So what’s an investor to do?

Robo-advisors tax-loss harvesting partners

First, we can look at what the robo-advisors are doing. You’d think it would be top-secret information locked away in a vault somewhere, but in fact Wealthfront has published a white paper spilling the beans.

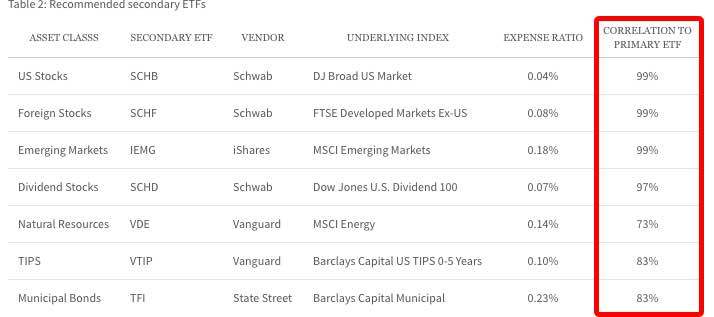

The white paper outlines Wealthfront’s tax-loss harvesting partners and the correlation between the two ETFs. Wealthfront has a list of primary ETFs for each asset class, but will switch to the secondary ETFs when the opportunity for tax-loss harvesting presents itself (and then presumably switch back when it can).

Table 2 contains the details on the correlation (you’ll have to read the paper to see the primary ETFs they use). As you can see below, the correlation between the primary ETF and its secondary “partner” ETF ranges from 99% to as low as 73%.

The white paper explains how Wealthfront handles the wash sale rules and their belief that the wash sale rules only apply if you’re swapping an ETF with another that tracks the same index from a different issuer.

In the case of applying tax-loss harvesting to a portfolio of index funds or passive ETFs, you need to use two securities that track different indexes to avoid violating the substantially identical clause of the wash sale rule. Swapping an ETF with another that tracks the same index from a different issuer (i.e. Vanguard vs. Schwab) would violate the substantially identical rule. As a result, you’ll see that the secondary ETFs presented in the table above are focused on tracking a different but highly correlated index from the recommended primary ETFs.

This is an aggressive position. When you have a 99% correlation between two partners, it starts to look “substantially identical”. On the other hand, Wealthfront has published this paper and the IRS hasn’t responded. Maybe “substantially identical” means identical? Without guidance, it’s hard to say.

Since there is no direct authority, it means by definition that reasonable minds can disagree on what is “substantially identical.” You can identify differences between funds managed by different institutions that track the same index (such as expense ratios, tax strategies, investment structure, etc.). On this basis, some might argue that mutual funds can never be substantially identical.

A more conservative approach (70% Overlap)

In a recent article in Barrons (paywall, use Google News), Eric Fox, who is described as a principle of Deloitte Tax, said something interesting that I hadn’t read before (bolding mine):

Although the wash-sale rule remains ambiguous, there may be an alternative standard that investors can use for guidance. In the 1980s, the IRS created the “straddle rules” to address a loophole in hedged long-short portfolios. For tax-loss purposes, the portfolios on the long side couldn’t be “substantially similar” to those on the short, which the IRS defined as having over 70% overlap. “Some people use the straddle-rules definition as a surrogate to apply to the wash-sale rule,” says Eric Fox, a principal at Deloitte Tax. “If two ETFs don’t have more than 70% overlap and they’re not substantially similar, how could they ever be considered substantially identical?” That should give loss harvesters some confidence.

The conservative calculation of only a 70% overlap is not in line with most of the articles I’ve read, not to mention the Wealthfront white paper quoted above. If the IRS were to determine that “substantially identical” means a threshold of not more than 70% overlap, the entire scope of tax-loss harvesting partners outlined by Wealthfront would be disallowed. Yet, he makes a good point. If two ETFs are not substantially similar, it seems hard to think they’d be deemed substantially identical.

My thoughts

Given the prevalence of the robo-advisors, I suspect the IRS will eventually provide guidance on what it means to be substantially identical (although it’s hard to imagine the IRS being able to monitor whether two securities are or are not substantially identical). Until then, I take the position that the wash sale rules were meant to prevent you from selling one security and basically repurchasing the same security the next day. Therefore, if there’s differences between the two securities, they are not substantially identical.

I think of it this way. If the IRS did challenge my position and I needed to make the argument that two securities were not substantially identical, could I make the argument with a straight face? If I could, then I’m fine with the trade. If I couldn’t, then I wouldn’t do it.

As an example, I wouldn’t be comfortable making the argument that the difference between the ETF version and the mutual fund version of the same Vanguard fund is not substantially identical. It doesn’t fly.

Likewise, I would never argue that swapping the Vanguard S&P 500 fund for the Fidelity S&P 500 fund is different, even if the underlying holdings are slightly different. It doesn’t feel right.

Tax-loss harvesting partners

So, after laying out what I wouldn’t do, what are some tax loss harvesting partners that I have used in the past?

For the large cap asset class, I’m comfortable swapping the Vanguard Total Stock Market (VTSAX) for the Vanguard Large Cap Index Fund (VLCAX). According to the ETF Research Calculator, the ETF versions overlap by weight by about 86%.

Similarly, I’d be comfortable swapping either of them for the Vanguard S&P 500 (VFIAX).

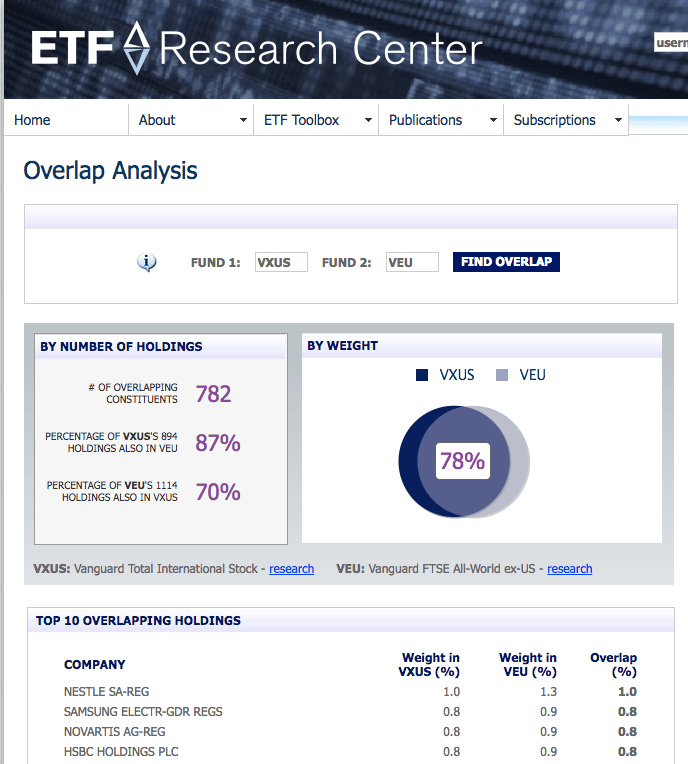

For international stocks, I’d consider swapping the Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund (VTIAX) for the Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Index Fund (VFWAX). The ETF versions overlap by weight by about 78%.

If you’re interested in other asset classes, such as emerging markets, dividends, TIPS, I’d check out the Boglehead list of substitute funds to see whether any meet your criteria.

Joshua Holt is a former private equity M&A lawyer and the creator of Biglaw Investor. Josh couldn’t find a place where lawyers were talking about money, so he created it himself. He knows that the Bogleheads forum is a great resource for tax questions and is always looking for honest advisors that provide good advice for a fair price.

I honestly haven’t thought much about it as I haven’t sold a stock for a loss in over a decade. Still I’d suggest going between funds that track separate indexes would be sufficient, especially if your not writing off losses in the millions. If and when they start cracking down and better defining it will be on someone prolifically doing so. Before that let your moral compass guide you as your chances of an issue are minimal.

Interesting – no losses at all? If you’re making regular investments in a taxable account, there should be plenty of opportunities to take advantage of tax loss harvesting since you can sell specific lots. So, for example, if you bought something today for $10,000 and the market tanks for the first six months of the year, you’d have the opportunity to sell that $10K lot for a loss, even if your investment portfolio is up as a whole (which, let’s be real, it better be!).

I’m holding mostly long term stuff in taxables with most new investments going into tax advantages. The little bit of taxable investmenys has so far been invested at the lowest points of the year. Admittedly that’s pure luck and a low sample set. A rising tide lifts all boats.

This is the first time I have ever read about vague, undefined terminology in the tax code and not been consumed with visceral hatred! Bravo!

For what little it is worth given my own lack of research on the subject, I approach my own endeavors with extreme conservatism (with the exception of my current allocation of 100% stocks) and would only be comfortable applying the definition from your quote of Eric Fox. I can accept that “substantially identical” is a higher threshold than “substantially similar,” so 70% overlap or less is clearly not substantially identical and would not be a cause for concern. But I do not trust my lack of expertise in the area to make a guess at how far over 70% the IRS may define “substantially identical,” and/or what other factors may be at play in the IRS’s choice to enforce the wash sale rule. It will be interesting to see how it develops; but I won’t be the one who suffers as it does!

Also, the ETF Research Center source that you used is interesting. I’m bookmarking that. Thanks for another great post!

Most lawyers do approach their endeavors with extreme conservatism! I’m not aware of the IRS ever challenging taxpayers whether an investment with substantially identical. Too many people make mistakes by repurchasing the exact same security during the wash sale period, so I think they have their hands full with that. If they did challenge a taxpayer, you’d think they’d then have to provide guidance.

Glad you found the ETF Research Center. Definitely worth a bookmark.

The IRS released Publication 564 in 2009 (https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/p564–2009.pdf) that reads:

Substantially identical.

In determining whether the shares are substantially identical, you must consider all the facts and circumstances. Ordinarily, shares issued by one mutual fund are not considered to be substantially identical to shares issued by another mutual fund.

For more information on wash sales, see Publication 550.

The Wealthfront white paper seems reasonable to me based on that reading, but now I suppose we can argue about the definition of “ordinarily.”

I go back to the argument I made in the article, which is that I try to imagine myself sitting across from an IRS auditor. As a lawyer, of course I’d be happy to argue that Vanguard’s S&P 500 fund is not substantially identical to Schwab’s S&P 500 fund. But I wouldn’t be surprised if the IRS auditor disagreed with me. If we see any action on the tax-loss harvesting point it seems likely that it’ll have something to do with the roboadvisors though.

“I’m not aware of the IRS ever challenging taxpayers whether an investment with substantially identical.”

Really?! That’s a relief, as in the recent CoronaVirus scare, I accidentally bought SPY as a replacement for VOOV, which the ETF Research Center comparison said was 99% Overlap by Weight. Should I go in and sell all of SPY and wait 30 days to clean it up?

Great article Joshua. Whoa boy, this topic is going to be hot this year!

I asked my municipal bond separate account manager to realize losses. Earlier this year they sold some positions and after 30 days bought the same positions, or sooner positions from different issuers. OK, legit.

But now they’ve started selling and buying ON THE SAME DAY, what seem substantially identical, but not purely identical securities. For example:

Sold: CALIFORNIA ST VAR P 5%29GO UTX DUE 11/01/29

Bought: CALIFORNIA ST VAR P 5%30GO UTX DUE 11/01/30

They have different CUSIP numbers and slightly different pricing. They are from the same issuer, have the same credit rating, and are priced nearly identically. It is common for a municipality to issue an offering like that, in series with 5-10 years of maturities, and all under the same offering memorandum.

Given apparent lack of IRS guidance to-date, it should fly. Still, gives me pause. Anyone here know of relevant guidance or precedence rulings, specifically for the bond market? Or have other thoughts?

(I’m a retired financial advisor with 36 years professional experience. Always learning.)