Like the tax code, rather than fix a problem, the government’s approach with student loans has been to enact a new repayment program without deactivating the old plans. While it’s good to have options, it can be a maze trying to figure out which program makes sense for you. Let’s go through each option. By the end I hope you will know which program is right for your federal student loans.

To pay or not to pay

Do you intend to repay the entire balance of your loans or to apply for loan forgiveness, either under PSLF or an income-driven repayment plan? Having a good debt management strategy is vital.

If you intend to repay your loans, you should probably refinance them in the private student loan market. Once refinanced, you can begin paying down the loans.

If you intend to have the entire balance of your loans forgiven, you’ll want to pay the least amount of money possible each month. This may have the effect of increasing the balance of the loans because of negative amortization.

It’s strange that the government set up such diametrically opposite possibilities. Either you pay off your loans and watch the balance decrease, or you don’t pay off your loans and watch the balance increase. There’s not a lot of flexibility to switch between paths once you start.

Standard repayment plans

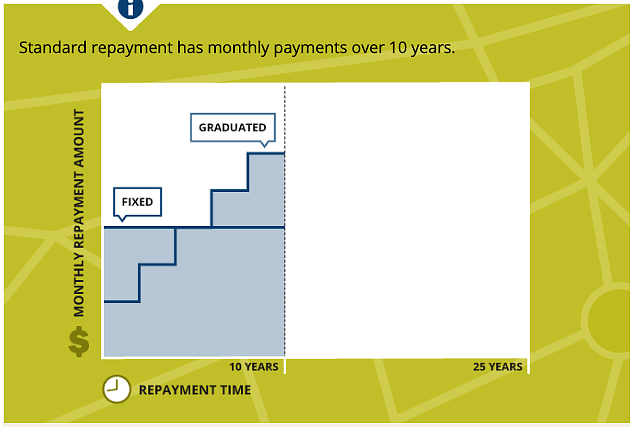

When the goal is to completely repay your federal student loans in 10, 25 or 30 years – and you have plenty of income to do so – the federal government provides two options: level repayment plans and graduated repayment plans.

Level Repayment Plan. The level repayment plan means you make the same monthly payment each month during the repayment term. Level repayment plans are similar to a standard mortgage. You have a monthly payment, a term (can range from 10-30 years depending on the loan) and once you reach the end of the term you will be debt free.

If you’re in Biglaw or otherwise have a high income, stick with the level repayment plan while you’re starting a new job. You should be refinancing these loans in the private refinance market but you may need a few months to get everything organized. Just start making monthly payments at the 10-year level repayment plan.

Graduated Repayment Plan. The graduated repayment plan means your beginning monthly payments are smaller than under the level repayment plan. Every two years your monthly payment amount will go up, meaning you halfway through the loan you will start making larger monthly payments than under the level repayment plan to “make up” for the smaller payments earlier in the loan.

Under the graduated repayment plan you will pay more total interest than under the level repayment plan. This is a good option if your income will be lower at first, such as for a federal clerk who plans to enter Biglaw after finishing a one-year clerkship.

Be mindful of lifestyle creep and your ability to inflate your standard of living because of a low student loan payment. With the graduated repayment plan, it’s easy to build a budget around a smaller-than-it-should-be monthly payment.

I can see the graduated repayment plan working for new Biglaw associates that have significant relocation, wardrobe and other expenses during the first few months of practicing law. You should be on track to refinance these loans as quickly as possible though, so it seems like a lot of hassle to call your lenders to set up a graduated repayment plan if it will only be in place for a few months. I’d just stick with the level repayment.

Income-driven repayment plans

If you’re not sure whether you will be able to pay off your loans – or if you do not have plenty of income to do so – the federal government provides for many repayment options based on your income.

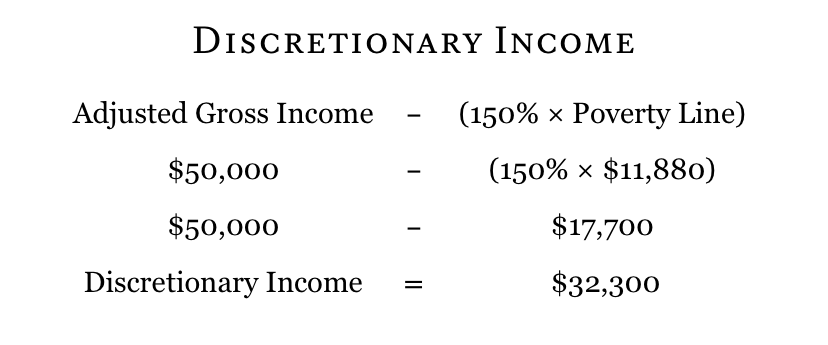

Income-drive repayment plans are based on your discretionary income. For these plans, your discretionary income is your adjusted gross income (as found on line 37 of your IRS Form 1040) minus 150% of the poverty line for your family.

At the end of an income-driven repayment plan, any remaining outstanding balance on your federal student loans is forgiven. However, the forgiven balance may be treated as taxable income. (aka the student loan tax bomb).

I’ll cover the student loan tax bomb in more detail later, as it remains up for debate whether the government will actually tax people for the forgiven balance of their student loans. As currently written, the law plans to do just that, which makes many income-driven repayment plans a significantly worse deal than you may think. Imagine a loan balance that grows to $200,000 after 25 years. Once forgiven, the government sends you a 1099 for “$200,000” worth of income. Not a pretty sight.

Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR). ICR is the original repayment plan based on income. It’s now outdated and not useful to most borrowers. Under ICR, a borrower pays 20% of their discretionary income towards student loans. ICR repayment plans last 25 years. Twenty percent of discretionary income is much higher than the income-driven repayment plans discussed below and given your incentive to minimize student loan payments (assuming you plan to have the balance forgiven), you’re better off paying a smaller percentage of your discretionary income.

ICR is only available for Federal Direct Loans (FFEL and Perkins loans are not eligible). Unlike any other income-driven repayment plan, ICR is available for Parent PLUS loans. This is a notable exception. If your parent is looking for relief on Parent PLUS loans, you may want to look into ICR. Parent PLUS loans aren’t available for any other income-driven repayment plan.

Income-Based Repayment Plan (IBR). Many public interest and solo lawyers are familiar with IBR. Payments under IBR are 15% of discretionary income. The repayment period is 25 years. IBR expands to include both federal and FFEL loans (Perkins loans still do not qualify).

There is a new version of IBR where the monthly payment is 10% of discretionary income and the repayment period is 20 years. However, this is only available to “new borrowers” as of July 1, 2014. If you had any outstanding federal loans as of July 1, 2014 (including undergraduate loans), you are not eligible. Practically speaking, most lawyers reading this will not be eligible.

Pay-As-You-Earn Repayment Plan (PAYE). The Obama administration extended further relief to borrowers through the PAYE system. Payments under PAYE are 10% of discretionary income. The repayment period is shortened to 20 years. Are you noticing a theme where each new program lowers the monthly payments and attempts to shorten the repayment period?

PAYE is a significantly better plan than either ICR or IBR because of the reduced percentage of discretionary income and shortened repayment period. However, PAYE has eligibility requirements that preclude many:

- Only Direct loans are eligible. FFEL and Perkins loans are not eligible.

- You must be a “new borrower” as of October 1, 2007. You’re a new borrower if you had no outstanding balance on a Direct Loan or FFEL Program loan when you received a Direct Loan or FFEL Program loan on or after October 1, 2007.

- You must have received a disbursement of a Direct or FFEL loan on or after October 1, 2011. Consolidating your loans does not meet the requirements of a “disbursement”.

Many recent law grads are not eligible for the PAYE program.

Revised Pay-As-You-Earn Repayment Plan (REPAYE). In the summer of 2014, the Obama administration announced plans to expand the PAYE system to include a wider group of borrowers. The new system, implemented at the end of 2015, is called REPAYE.

REPAYE is only available for Direct loans but removes the requirement for “new borrowers”. This significantly expanded the program and made many recent law grads eligible. Payments made under REPAYE are the same as under PAYE (10% of discretionary income).

Another benefit of REPAYE is that the government will cover 50% of accrued but unpaid interest on both subsidized and unsubsidized loans. If your monthly payments are not covering interest, this should help keep the loan balances from ballooning. I could see this being helpful if you think you may switch to full repayment in the future.

But everything about REPAYE is not great. There are some significant differences.

First, REPAYE has a 25-year repayment period for lawyers (it’s only 20 years if you only have undergraduate loans, but the vast majority of readers of this blog will have graduate loans). Five extra years of repayment is a lot of money.

Second, if you are married, REPAYE counts your entire joint income – regardless of whether you file as jointly or separately – in determining your discretionary income. This is a big deal for married couples, particularly when one spouse earns more than the other. For instance, an associate in Biglaw married to a public interest lawyer will likely have a combined income high enough to make the 10-year standard repayments, thus negating the benefit of being on an income-driven plan. For this reason, REPAYE eliminates many married borrowers.

Negative amortization

Regardless of which income-driven plan you select and depending on your loan balance, there is a high likelihood that your monthly payments will not cover the interest generated by the loans (otherwise known as negative amortization).

If your monthly payments do not cover your interest, your loan balance will grow over time. I’ve had many lawyers tell me how painful it is to make $500 monthly loan payments only to watch their balances rise.

If your plan is to receive loan forgiveness at the end of the loan, you are incentivized to make the smallest monthly payment possible which means it’s technically a good thing you’re not covering the interest payments. However, it’s a weird quirk of the system that borrowers are forced down one of two diametrically opposed paths.

Either you plan to pay off the loans, which means you’ll refinance them to get the lowest rate possible and make aggressive monthly loan payments. Or, if you plan to apply for forgiveness, you want to pay the least amount possible per month and could easily end up in a situation where your original loan balance of $100,000 has doubled to $200,000 at the time of forgiveness.

What happens if you want to switch between these two options at a later point in time? It’s going to be problematic if you’re on some type of income-driven repayment plan with increasing loan balances and you decide to pay off your loans between years 10-15 because of the possibility of a negative amortization and a much higher loan balance.

Therefore, borrowers need to give a lot of thought to what repayment plan makes sense for them over the long term. While income-driven repayment might make sense now, will you want to pay off the loans later in your career? Waiting 20 or 25 years for loan forgiveness means many lawyers could have student loans in their 50s.

If you think you will eventually pay off your loans, you need to avoid negative amortization and make the highest monthly payments you can afford regardless of the percentage of discretionary income required by your income-driven repayment plan.

Finally, the income-driven repayment plans all require you to re-certify your income each year by supplying updated income information to your loan servicer.

Joshua Holt is a former private equity M&A lawyer and the creator of Biglaw Investor. Josh couldn’t find a place where lawyers were talking about money, so he created it himself. He is always negotiating better student loan refinancing bonuses for readers of the site.