At a high income level, it may seem obvious to maximize your tax-advantaged accounts. However, many readers struggle with student loan debt (even when they’ve refinanced their law school loans) and consciously make a decision to forgo 401(k) contributions to instead accelerate debt repayment.

When I was a junior associate, I chose to prioritize student loan debt repayment. In hindsight, I should have been doing both. A Biglaw salary is plenty of money to contribute the maximum to a 401K and still have plenty left over to send to student loans.

Here’s the article I wish I would have read when I first started in Biglaw.

What does maxing out your 401K look like? Not as bad as you think

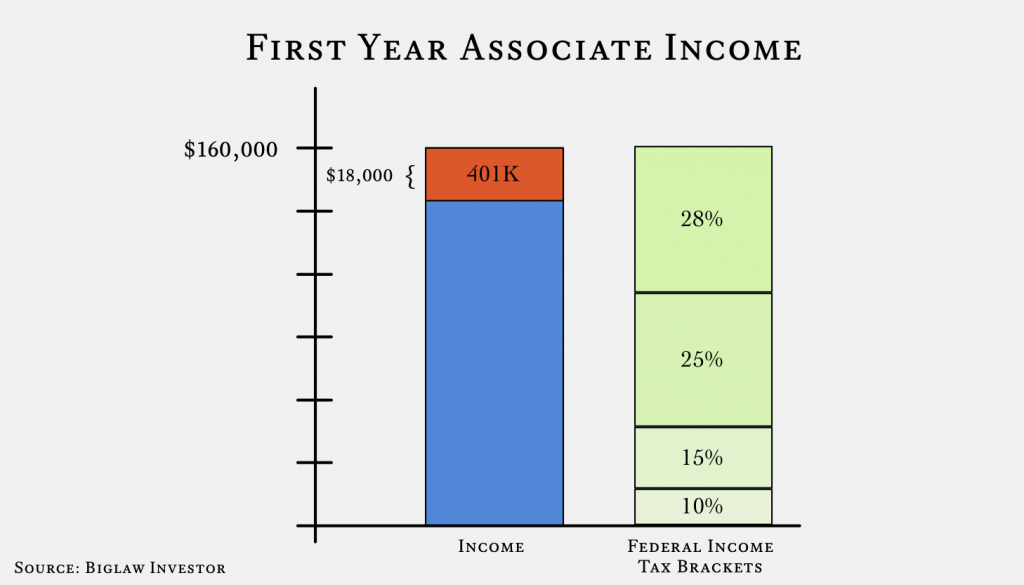

Contributing the maximum amount to your 401K means paying $1,500 a month in pre-tax dollars ($1,500 × 12 months = $18,000). According to an online calculator, a typical first year associate would see a reduction in their monthly take-home pay of about $900. In other words, you give up $900 from your monthly paycheck but see $1,500 deposited into your 401K.

$900 is not a lot of money, especially when you’re jumping from making $0 to making $[table “19” could not be loaded /]

. You won’t miss the money.

Reason 1: taxes are a drag

Taxes are a major drag on your ability to accumulate wealth. There’s two concepts to understand before we go any further: marginal tax rate and effective tax rate.

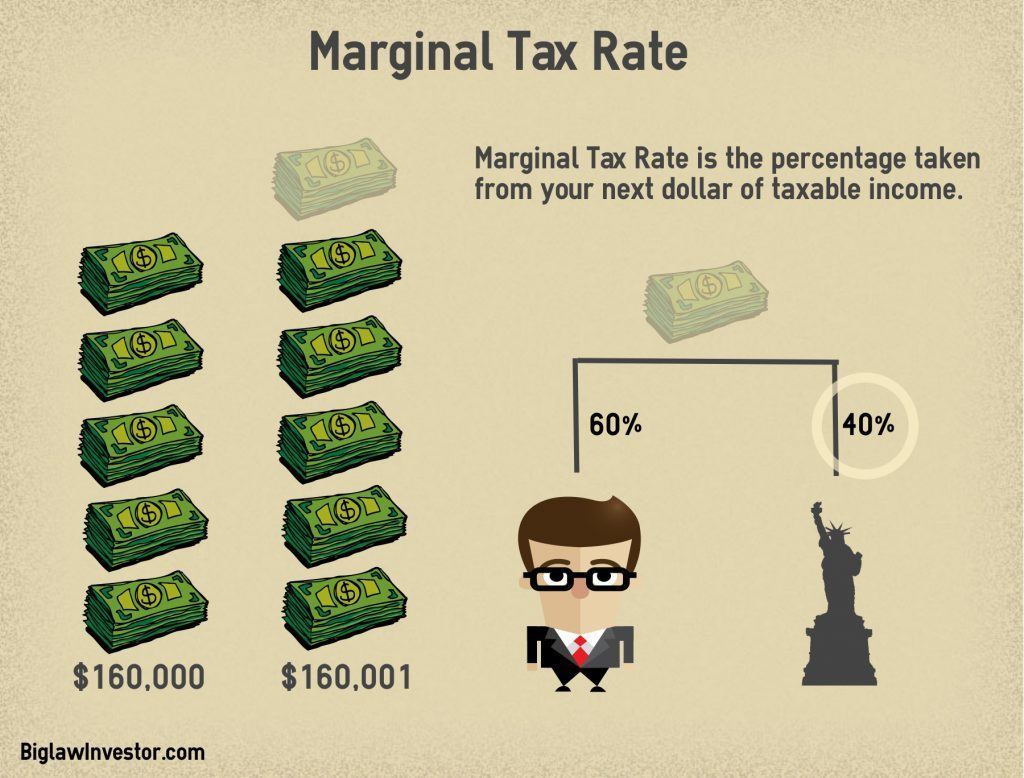

Marginal Tax Rate. Your marginal tax rate is the percentage taken from your next dollar of taxable income. In other words, if you earn an additional dollar how much will go to taxes?

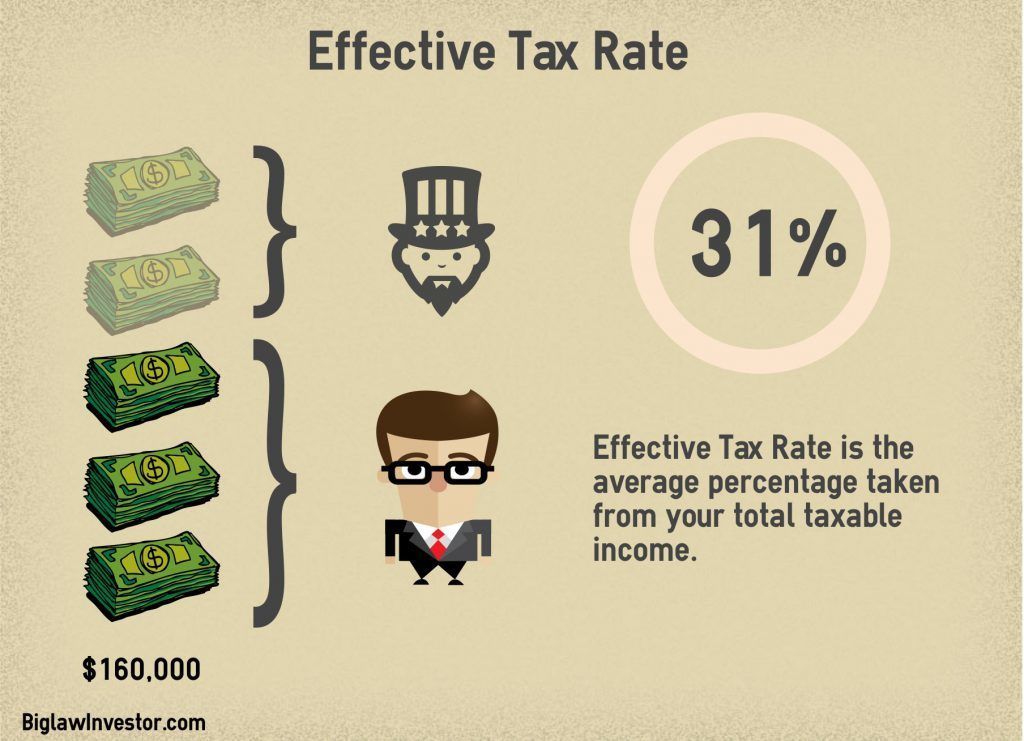

Effective Tax Rate. Your effective tax rate is the average percentage taken from your total taxable income. In other words, what percentage of your total income is paid in taxes?

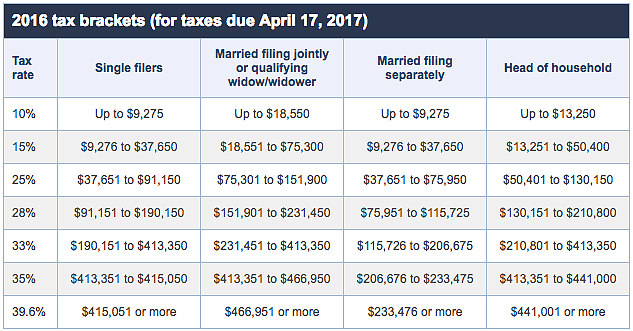

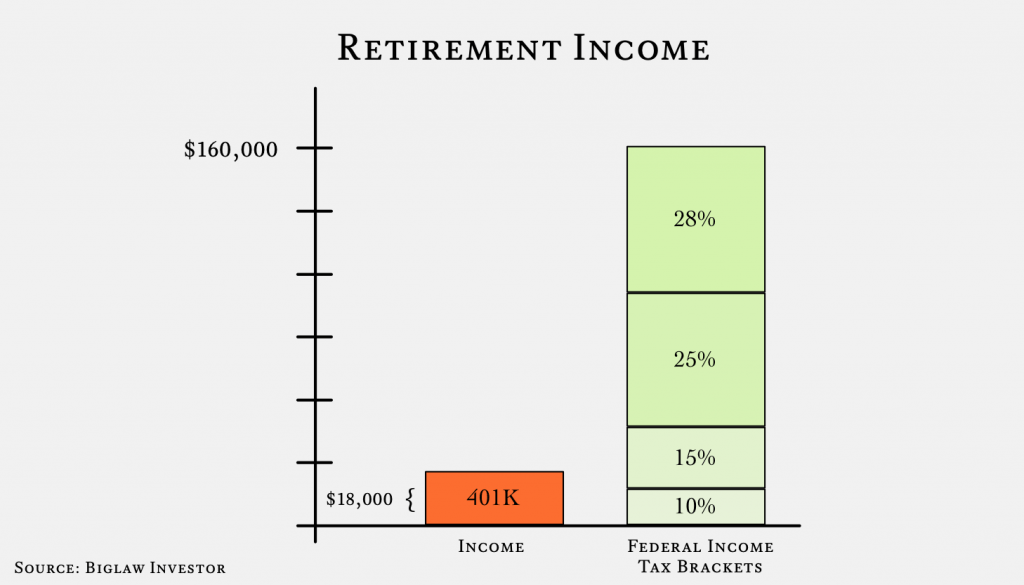

Why is There A Difference? There’s a difference between your marginal tax rate and your effective tax rate because the United States tax system is progressive. You pay 10% on your income between $0 and $9,275. You pay 15% on your income between $9,275 to $37,650, etc.

If you think about earning dollars throughout the year, it’s easy to see that the first dollars you make are taxed at a lower rate than the dollars you earn at the end of the year.

Let’s assume you have a marginal tax rate of 40% (including state and local taxes). A 40% marginal tax rate means you will pay $0.40 in taxes for each additional dollar earned.

Saving for retirement means diverting those very last dollars into a tax-advantaged account where you pay no income taxes. Therefore, you’ll save $0.40 for each dollar deposited into a retirement account.

But, won’t I pay taxes on withdrawal?

Yes. Funds in a 401K grow tax free, but are taxed as income at the time of withdrawal. You can’t escape paying income taxes on this money.

The key concept is that when you contribute to a 401K you save paying taxes at your marginal rate, but when you withdraw from your 401K you will pay taxes at your effective rate.

Let that sink in. It’s the most important point in the post and a point I missed as a junior associate.

It’s a great deal to avoid paying 28% (plus state and local taxes) now if you will only pay 10% tax later. You’re taking advantage of tax arbitrage.

In retirement, not only will your effective tax rate be lower than your marginal tax rate today (even if taxes go up), but you may be living in a lower tax environment.

For example, I work in NYC (Federal/State/City Tax) but will probably retire somewhere warm. Neither Florida nor Texas have state income taxes. My marginal tax rate today is 45.848% (keep in mind that you still must pay FICA taxes on 401(k) contributions). I’m confident my effective tax rate will be lower in retirement.

Some of you might be thinking that it’s possible my marginal tax rate might be higher in retirement. Tax rates could go up. I could retire in NYC. My income could be large. Those would all be good problems to have (except higher tax rates) and don’t change the calculus that it’s much more likely that your marginal tax rate today is higher than your effective tax rate in retirement.

Reason 2: you only get access to tax-advantaged space once

If you decline to participate in a 401K plan in any given year, you do not have an opportunity to participate in the future (i.e. other than being able to contribute an extra $6,000 after the age of 50, there are no catch-up provisions). When you’re young, you may think that this isn’t too important.

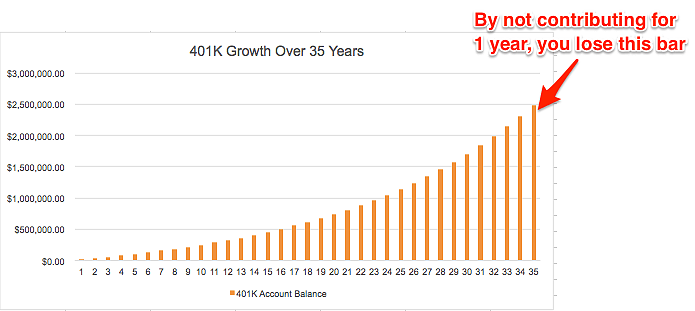

It’s actually very important. By skipping a year of contributions, you shorten the time horizon for your investment returns. As a young investor in the accumulating phase, your greatest asset is time. You want your dollars to work for as long as possible, thus taking advantage of the value of compound interest.

Hypothetical.

Bill is 30 years old. He will begin withdrawing from his 401K when he reaches 65, giving him 35 years of growth.

Alice is 30 years told. She will begin withdrawing from her 401K when she reaches 65, giving her 35 years of growth. Unlike Bill, she decides to delay contributing to her 401K account for only 1 year.

Bill contributes $18,000 each year for 35 years. He has $2,488,263 when he turns 65.

Alice contributes $18,000 each year for 34 years. She has $2,308,657 when she turns 65.

Not contributing in year 1 results in a $179,606.04 loss by shortening the growth of your money between year 34 and 35.

For each year you don’t contribute, you’re cutting off a year at THE END of the growth chart.

Reason 3: you can always access your money if disaster happens

You own the money in your 401K account and can always access it. Money that is withdrawn prior to the age of 59.5 typically incurs a 10% penalty tax unless a further exception applies.

So while it’s not an elegant solution, you have access to this money should you absolutely need it.

Reason 4: you won’t miss the money

Setting up your 401K account today will help you grow into your income. Because $[table “19” could not be loaded /]

is more than you’ve ever made in your life, you will not miss the money deposited into your 401K.

Do this even if it slows down your student loan repayment. If you’ve found a good interest rate when refinancing your student loans, it’s worth the “extra” cost of the interest as you pay off the student loans at a slightly slower pace. Do this even if you think you might leave Biglaw in 2 years. Your income is too high not to take advantage of the tax shelter.

Reason 5: your firm’s 401K plan is good enough

Sometimes people decide not to contribute to their 401K plan because they don’t like the fund options. The 401K plan may have high fees or offer lukewarm investments like industry specific funds rather than broad index funds.

This is a reasonable concern. Paying high fees will have a major impact on your future returns and you should minimize them. However, the advantages to contributing to a 401K plan far outweigh the drag caused by an excessive fee of 1-2% per year, particularly when you are in the accumulating phase. Most 401K plans will have at least one low-cost index fund, even if it’s the S&P 500.

If that sounds like your plan, pick the S&P 500 Fund and max it out. When you leave the firm, you will have the opportunity to roll your 401K account to a new provider where you can make better selections.

Joshua Holt is a former private equity M&A lawyer and the creator of Biglaw Investor. Josh couldn’t find a place where lawyers were talking about money, so he created it himself. He spends 10 minutes a month on Empower keeping track of his money. He’s also maxing out tax-advantaged accounts like 529 Plans to minimize his taxable income.