I’ve started to see some questions on asset location, both in the comments section and via email. There seems to be some confusion about whether to place certain assets inside tax-protected or taxable space.

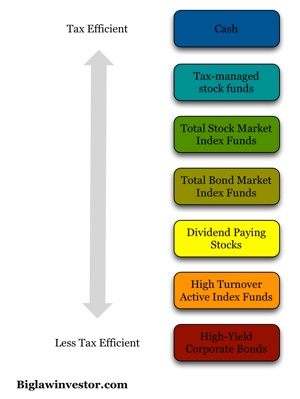

The prevailing view is that you should put tax-efficient asset classes, such as stock index funds, inside a taxable account and put tax-inefficient asset classes, such as bonds, in your tax-protected accounts.

Unfortunately, this oversimplifies the analysis considerably. You also need to take into consideration the expected return of the asset class.

Tax drag is slowing down your portfolio

First, this is an advanced topic. If you’re accumulating assets and currently only investing inside your tax-protected accounts (like a 401(k), Roth IRA and HSA), then there’s no need to take a deep dive into worrying about asset location yet.

But, if you have a taxable account, you may want to consider where you should be putting different assets.

Different asset classes have different levels of tax efficiency. For example, some would say that bonds or bond funds are tax-inefficient because almost all of the return comes from the yield, which is taxed as ordinary income.

If you have a bond fund in your taxable account, all of the interest returned that year is going to be taxed at your ordinary income rate, even if you have no need or desire to receive the income. Over time, this can cause quite a drag on your portfolio as the taxes on the dividend yield eat away at your overall return.

A more tax-efficient asset class would be stock index funds. Most of the gains in a stock index fund are locked in as capital appreciation. Your index fund continues to grow and you only pay taxes when you sell, therefore reducing the tax drag to the dividends and capital gains paid out at the end of the year, many which may be taxed at the capital gains rate anyway. Only a small part of a stock index fund pays out as dividends or capital gains.

So at this point, it seems pretty clear, right? Tax-inefficient asset classes should go into tax-protected spaces. But the general rule breaks down when you consider the the expected return of the investments.

Bonds go in taxable

Let’s consider an investor that maintains an asset allocation of 50% in stock index funds and 50% in bond index funds. Our investor pays a marginal federal tax rate of 33%. Further, we’ll assume that the stocks have a 7% return while the bonds return 3%. Let’s calculate the return on these portfolios over 30 years, assuming no rebalancing.

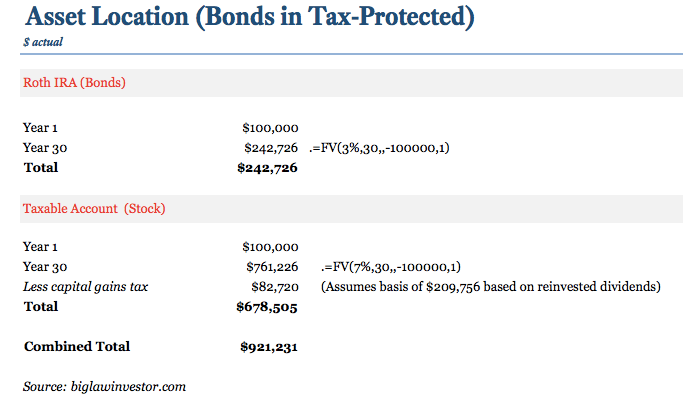

Example 1: Bonds in Roth; Stocks in Taxable

The total portfolio returns $921,231 over 30 years. Not bad. You keep the entire return on the bonds thanks to their tax-protected space and you pay minimal capital gains tax in the taxable account.

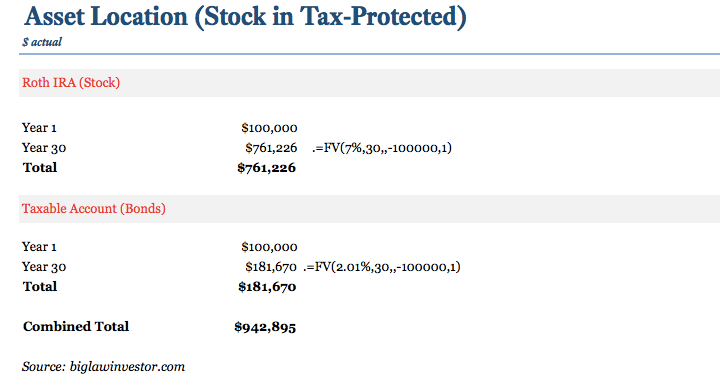

Example 2: Stocks in Roth; Bonds in Taxable

Bonds take the hit in this portfolio and only return 2.01% (since we must reduce the 3% assumed return by the investor’s marginal tax rate of 33% – this is a great example of the tax drag in action). Meanwhile, the stock portfolio climbs high and we get to take all of the profit without paying any capital gains taxes.

The second portfolio returns $942,895. That’s $21,664 more dollars than the first portfolio or an extra 2.35% return. And that’s when you placed the bonds – the more tax-inefficient asset class – in the taxable account.

But it makes sense. The expected return matters. If you put your stocks in a taxable account, you’re betting that the tax-free return on the bonds will be greater than the taxed return on your stock. If you switch positions, you’re betting that the tax-free return on the stocks will be greater than the taxed return on the bonds.

For that reason, it’s an incomplete discussion to only consider the tax efficiency of an asset class when deciding where to put it. You must consider both its tax efficiency and its expected returns.

The end result is that you need to run the numbers yourself. Changes to your expected returns on bonds, your expected return on stocks, tax rates, etc. will have an impact on the conclusions. The point is that there’s no reason to take a hardline view that all tax-inefficient assets belong in tax-protected accounts since that isn’t always the case.

Joshua Holt is a former private equity M&A lawyer and the creator of Biglaw Investor. Josh couldn’t find a place where lawyers were talking about money, so he created it himself. He spends 10 minutes a month on Empower keeping track of his money. He’s also maxing out tax-advantaged accounts like 529 Plans to minimize his taxable income.